"'I fear, my beloved girl,' I said, 'little happiness remains for us on earth; yet all that I may one day enjoy is centred in you. Chase away your idle fears; to you alone do I consecrate my life, and my endeavors for contentment.'" -- Page 140

Let's get a group 'Aw!', shall we? Awwwwww! Alright, that felt good.

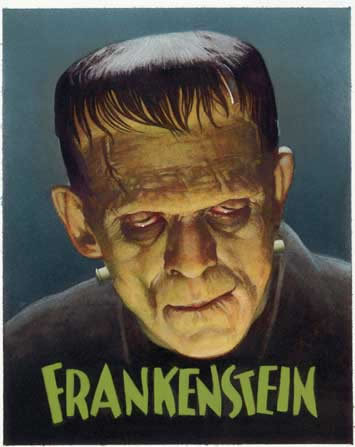

First, I take back everything I said about Victor! He's amazing, the best, wonderful, a true Gothic romantic! The letter he writes to Elizabeth while returning to her is beautiful poetry ripped straight out of a Taylor Swift love story (no pun intended). I know I thought it was a little creepy at first, the incestuous relationship between Victor and Elizabeth, brother and sister, cousin and cousin. Call it what you'd like, they aren't related. They reveal their mutual love for each other in what is probably the cutest way possible, and I can appreciate that. But to be honest, I'm just glad something interesting happened in this story besides Franky killing one of Victor's kinsmen and then Victor moping about it for three chapters straight. All in all, the future is looking up for Victor if he marries Elizabeth, and if he does as he promises, which is tell Elizabeth everything the day after they're married, then maybe he can finally get some support in this novel from someone other than his own inner conscience. I swear his biggest problem during the entire course of events was never letting someone else in. You gotta let that stuff out, man.